Rafael: I’m going to talk about photos again because they were proof of something. I won’t say evidence of being alive, but close to that.

Greg: For you, it is not a stretch to say it was the difference between being and nothingness.

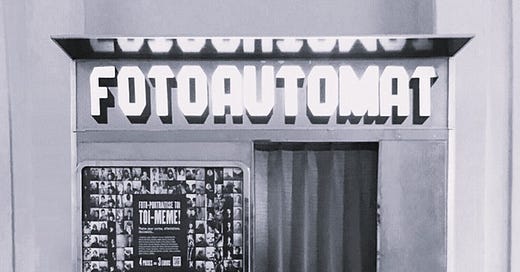

Rafael: Sort of, yes. There were photo booths in some metro stations. They were cheap too, five francs, wasn’t it? For four photos.

Vintage Paris Metro Photo Booth

Greg: Yes, it was five francs. But at the time I would not have said ‘cheap’. I did not indulge myself quite as often as you did.

Rafael: You’d get four prints, either all the same or four different ones. Going into these booths became a habit of mine.

Greg: Possibly an addiction?

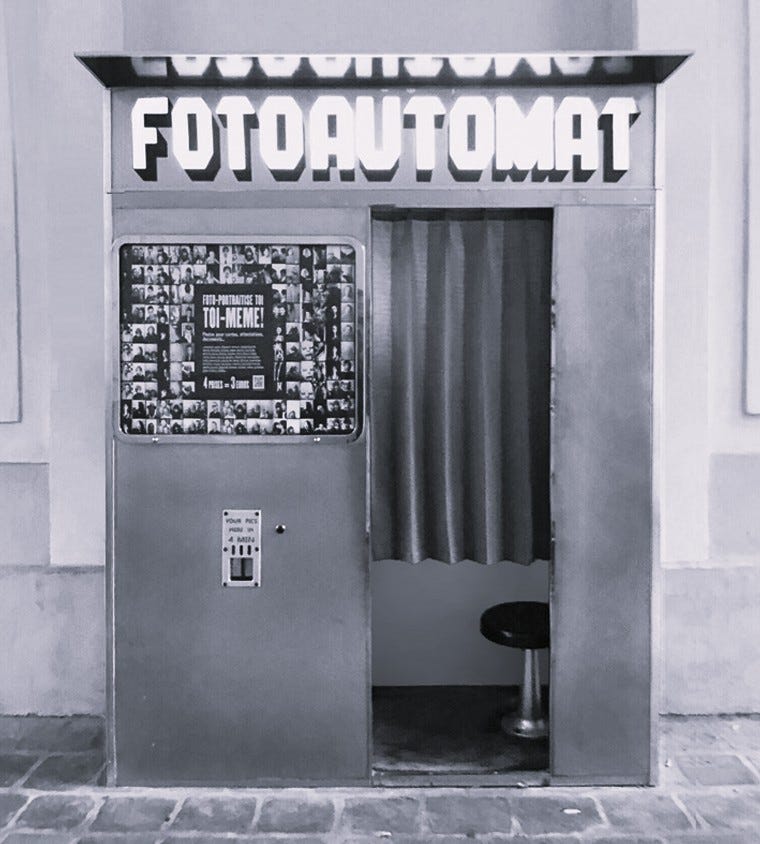

Rafael: I think you and I even took a few together.

Greg: Many times.

Four Shots from a Metro Photo Booth, Paris 1977

Rafael: I also took a few photos with the staff at Chez Haynes. I did photo booths on impulse, though. ‘Oh, there’s a photo booth, I haven’t taken a shot of myself for a few weeks, I’ll go in now’ as if to prove to myself I was here, alive and kicking in Paris. I saved these photos in a Manila envelope. Time passing was captured in those brown envelopes, a prized possession of mine.

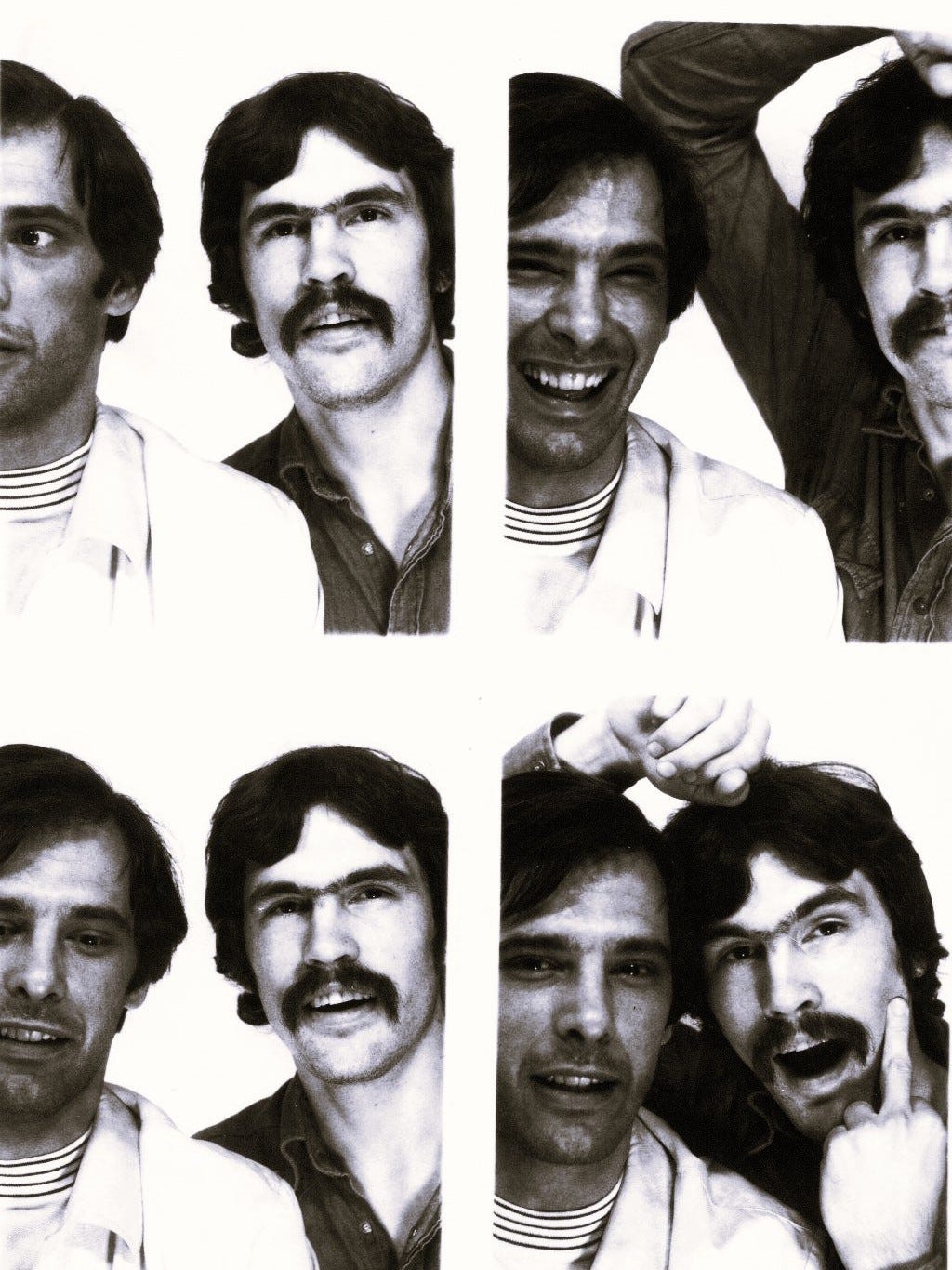

Greg: I recall you always taking photos of yourself in these photo booths, often with staff and friends from the restaurant. Or with whoever happened to be with you at the time. Whenever we were on the metro together, changing metro lines or exiting, you would see a booth and suddenly track straight toward it. A compulsion. In hindsight, it was a bit strange, given we had access to your darkroom. But the instant response of the booth was pleasing in an existential way. And we had fun, jumping in and out of the booth, sometimes making faces, while waiting for the four distinct flashes to pop. I still come across one or two of them lurking in my papers and mementos from those days. I may have teased you for your fixation on it, but I don’t remember questioning it. I thought you were using some of them as studies for the larger self-type portraits of the photo-paintings you were making at the time: I remember titles like Portrait-Paysage, Portrait-Saut, Portrait-Triptych, Self-Portrait with Sun Glasses. I still remember the stark, black and white intensity of the paintings, many situated in empty rooms with just a chair or projection on the wall. Excellent stuff, ‘formidable’ or ‘vachement chouette’ as the French would say back then.

“Self-Portrait with Sun Glasses” 1976 120x101cm photo-sensitive canvas

Rafael: The relationship between the photo booth pictures and my photo-canvases was philosophically intimate. By that I mean that both seemed more real to me than oil self-portraits. Maybe because the photos were a chemical result, scientific, atomic even. I played a smaller role technically with those results than when I painted a self-portrait. With the photos I was once removed. They were nearly automatic. I pushed a button and presto!

Greg: I don’t remember exploring the symbolism of the imagery very deeply at the time (not consciously), but it does appear to have permeated much of the work we were doing. Cameras, typewriters, paints, props, photos filling empty spaces and rooms became an ongoing theme. Perhaps that’s the same for all artists and writers. Filling the void with something. The two covers which you designed for my poetry books were of completely empty rooms and a large theatrical space of empty chairs.

Covers of two poetry books, Orleans Press, Paris

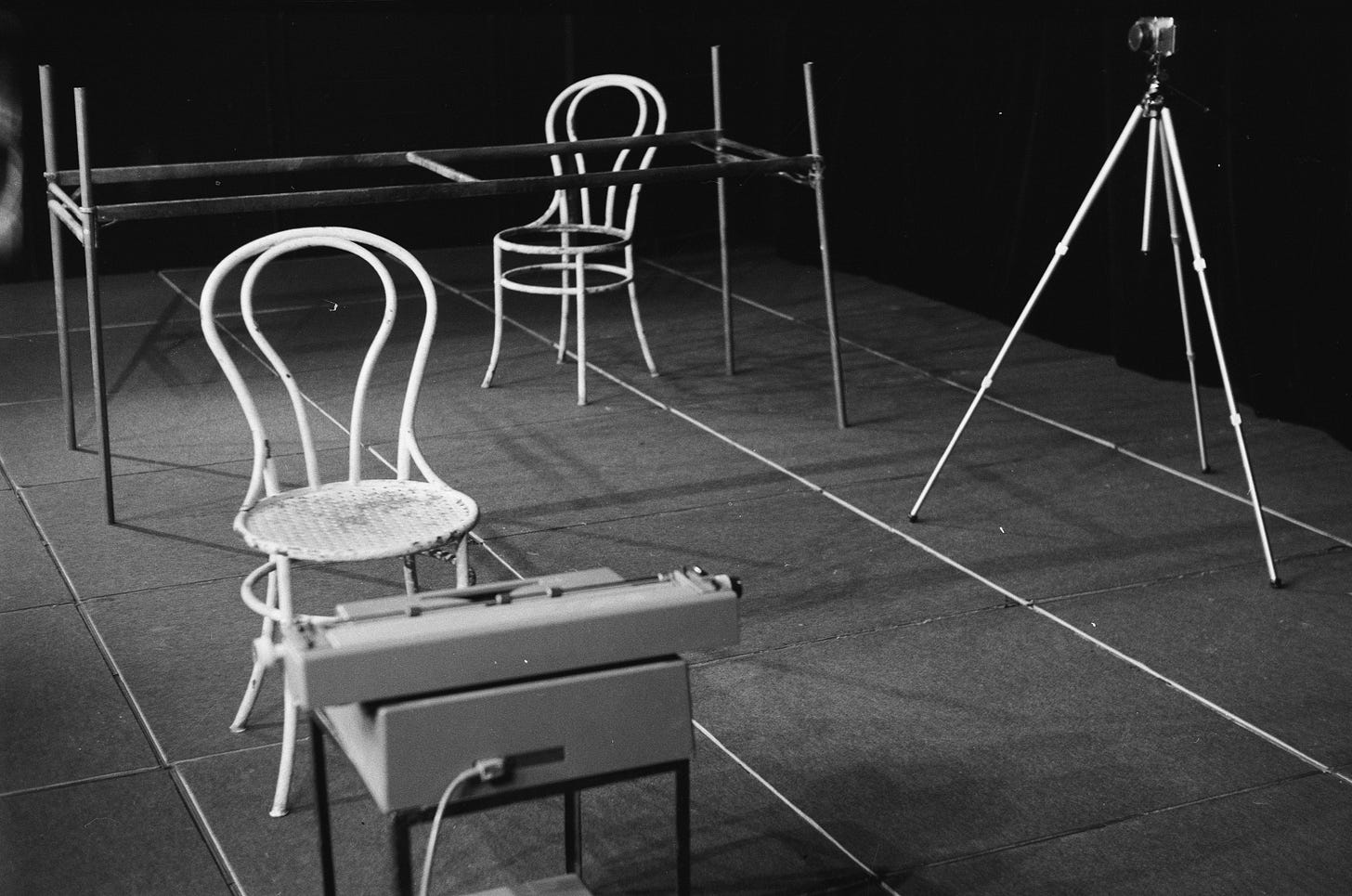

Greg: In my plays and in many of your paintings, emptiness was a persistent theme. Words and pictures filled them. The set of Black to Black consisted of just a black metal table with no top, a white metal chair with no seat, a camera on a tripod, and a large electric typewriter.

Set of Black to Black - Table, Chairs, Camera, Typewriter

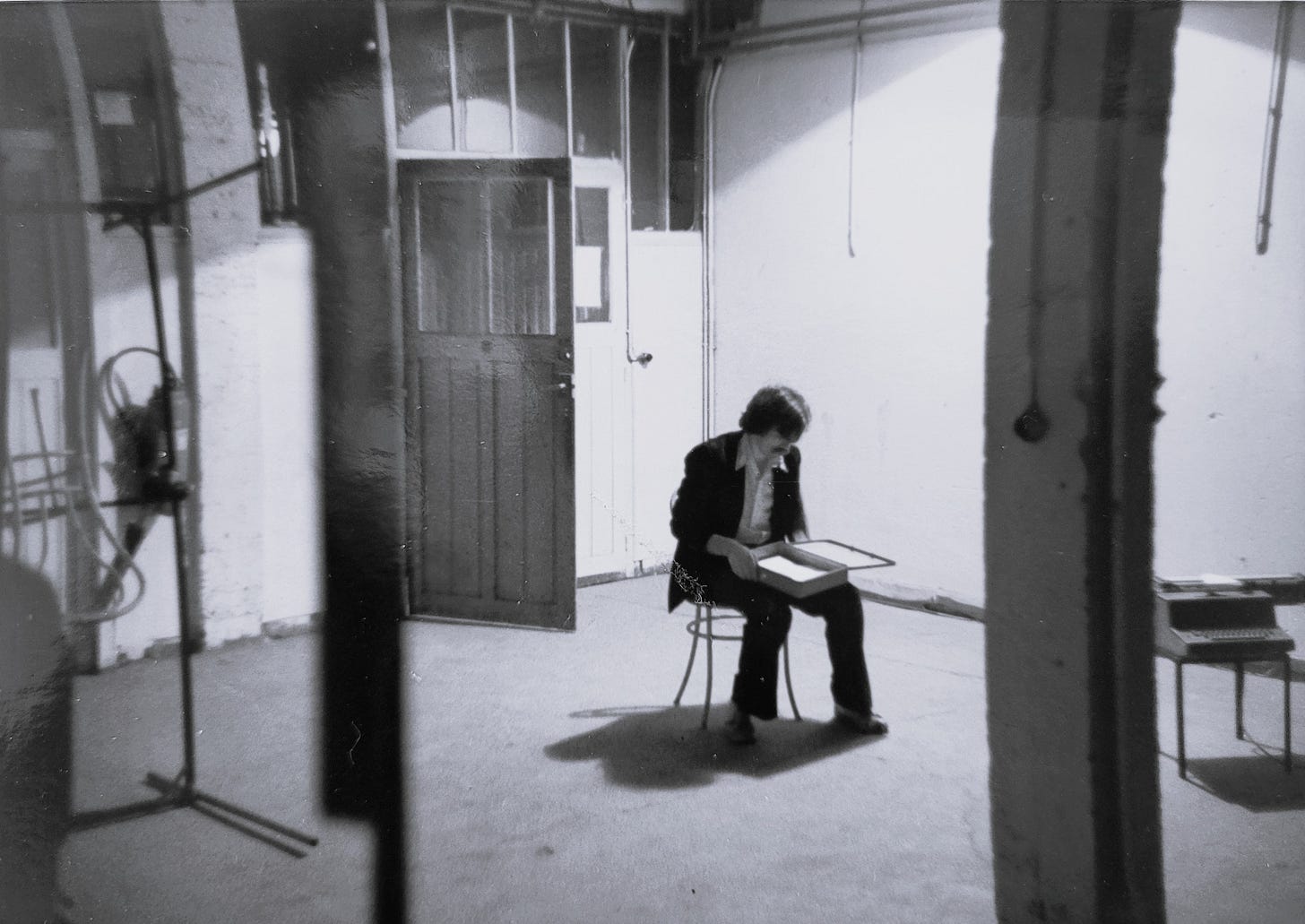

Greg: The set of One Day in May was just a pile of thick ropes and hundreds of rags with which the actors constructed the different spaces they lived in very much alone. The most dramatic empty space that we staged Black to Black in was at the Farideh Cadot Galerie; her second space. At 11 Rue du Jura. She called L’Espace 13. Maybe because it was in the 13th arrondissement. It was an ominous, large, abandoned office or apartment with dark empty rooms which she had rented or was temporarily given to exhibit art and performance pieces beyond the usual paintings and sculptures of her contemporary gallery. It looked like it was on the verge of being torn down. The individual props were in different rooms and the audience followed me around as I performed.

Black to Black performance - Farideh Cadot Galerie, 11 Rue du Jura, Paris 1979

Rafael: That was a success.

Greg: It was a lot of fun. Wonderful to perform. And it worked. But it was also a one-night run. No money: expected or offered. That was pretty much how I defined success back then.

Rafael: But my show at UNESCO was a disaster.

Greg: Disaster? Are you kidding? Two-week run. Large space in a prestigious Paris building. Professional catalogue.

Rafael: That was the best part of the show. Your catalogue text was so perceptive. As for the actual pieces, it was a great opportunity which I blew. A New York collector had arranged for me to show my work in the big central hall at UNESCO. You helped me assemble some fifteen large pieces—and they were large, two and a half meters high by two meters wide. Each piece consisted of large photos taped together. We pinned the large collages to the wall. UNESCO paid for a small catalogue, and you wrote a wonderful, insightful text. I don’t remember the opening, or if there even was one.

Catalogue for Rafael’s Outsider Paintings Show, UNESCO, Paris 1978

Greg: Again, I remember an opening. And this memory is very clear and distinct. (So, it meets Descartes’s criteria for evidence.) There was a good size opening crowd, wine and cheese, and the usual hubbub you hated. And the pieces all looked great.

Rafael: What I remember is that in that well-heated space the tape holding some of the photos together softened and the collages came undone, fell to the floor, like crumpled junk.

Greg: That happened before the crowd arrived.

Rafael: We eventually fixed them with staples.

Greg: Problem-solving. That’s what we did. That is what we were always doing. I remember it being a few hours of panic, but the fix worked. The show looked great. And you have forgotten a further highlight of the show. Along with the 18 large paintings, you also exhibited ten amazing wooden box sculptures—ten wood boxes (I remember them looking like crates that whisky bottles or upscale wine had been packed in), each uniquely painted and containing sculptures or collages of rags, paint, wood, and wire. I referred to them as mini ateliers, but they could equally have been seen as abstract set designs or studies for One Day in May. That whole UNESCO show resonated with so many of the remarkable materials and images and ideas that grew out of the Chez Haynes years: the photos, the rags, the x-rays, the ateliers, the portraits, the exploration of self.

Wooden Box Sculptures, Rafael Mahdavi, UNESCO show

Rafael: Now I tell myself, live and learn, but at the time I was mortified and ashamed. As to the boxes which were later exhibited at the Gimpel Fils Gallery in London, they were built out of cheap particle board. I arranged balsa wood pieces in them as in a three-dimensional collage. I still have them and still find them beautiful. They were also a nod to David Smith, the American sculptor, and his notion of sculptural drawing-in-air.

Greg: So, not a disaster at all. It is amazing what memories our emotions insist we prioritize. Perhaps that is because, all too often we remember through the eyes of our worst critics. Ourselves. But that is not an absolute of our being.

Rafael: I also remember the surreal scene of that exhibition space between noon and four in the afternoon. On all the couches, and there were plenty of them, were diplomats, all men, stretched out for their siestas, and snoozing and snoring.

Greg: Enjoying a little nothingness. Like the Clodos on the metro grates. It’s vastly underrated.

“Enjoying a little nothingness”, Paris Street

Rafael: I wondered at the time if I should be incensed or admiring of these well paid diplomats, on taxpayers’ money of course, in thousand-dollar suits, some potbellies protruding, sleeping off their post-lunch fatigue.

Greg: The ultimate positive critique. Not just ‘I can live with these paintings’, but also ‘I can sleep with them.’ Much better than the faux ‘oohs’ and ‘aaahs’ about Rothko and others which you loathed.

Sleeping with Rothko

Rafael: Good point. Maybe that was usual. In hot countries I myself do take siestas. So, I suppose chacun son vice, as Talleyrand said.

Greg: Siestas, naps, snoozes. They are the ultimate vice. The real stuff of being. Something I am now learning to fully appreciate.

NEXT WEEK: Da VINCI’s SHOES

Thanks for reading The Dishwasher Dialogues!

The Dishwasher Dialogues is AI-free and free to subscribers. Posts every Sunday.

The Dishwasher Dialogues - THE BOOK

Happy Father’s Day … really enjoyed it. Thanks

Filling the void with stuff and make it real it’s a ongoing task